Lost In The Amazon – The Hunt For Colonel Fawcett

In 1925 British explorer Colonel Percy Fawcett entered the Amazon jungle. Searching for a lost city, he was never seen again. Writer Duncan JD Smith picks up the trail.

With the new action adventure film The Lost City of Z due for release shortly (Spring 2017), now is the time to celebrate its enigmatic and reluctant hero, Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett. A fearless geographer and rogue archaeologist, his daredevil exploits inspired Conan Doyle’s The Lost World and more recently the adventures of Indiana Jones. His unexplained disappearance in the Amazon Jungle has become the stuff of Boy’s Own legend.

For every Colonel Fawcett known to the world, there are a hundred such who have disappeared and remain entirely unheard of

The Making of an Adventurer

Percival Harrison Fawcett was born in 1867 in Torquay in the English county of Devon. His Indian-born father, Edward, was something of a rake, an equerry to the Prince of Wales, and a drinker. Young Percy undoubtedly inherited his father’s sense of adventure but from an early age he disproved of his racy lifestyle. Instead he became a serious and academic loner.

Aged nineteen, and against his will, he took up a commission in the Royal Artillery and was posted to Trincomalee in Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka). He served brilliantly and it was there that he met his future wife, Nina. But it was how he filled his leisure time that was to really set the tone for the rest of his life. Leaving his fellow officers to their drinking, gambling, and fraternising with the locals, he would wander off into the jungle interior of the island, seeking out ancient ruins and recording mysterious inscriptions.

In 1901, whilst working for the British Secret Service in Morocco, Fawcett brushed up on his surveying, a skill he had first taken up at the Royal Geographical Society on London’s Savile Row. This was to prove invaluable when in 1906 he travelled to Amazonia at the Society’s behest to map the jungle border between the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso and Bolivia. The area was rich in rubber plantations and without accurate borders it was feared dangerous disputes would result over their exploitation. With the mass production of automobiles in full swing, the demand for rubber was enormous.

Renowned for his remarkable stamina and resistance to disease, Fawcett was in his element. Between 1906 and 1921 he embarked on no less than seven South American mapping commissions contributing much to the Society’s ongoing mission to map the world. He was appalled, however, by the way in which some plantation owners treated the Indians of Amazonia. By contrast Fawcett appears to have got along well with them, using his patience, courteousness, and, of course, gifts to good effect. During one survey exploring the Heath River in Bolivia, for example, his team was attacked by Indians of the Guarayos tribe firing 7-foot-long (2,10 metres) arrows. Rather than returning fire one of them played an accordion and, when the attack was halted, Fawcett addressed the Indians in their native tongue. The Indians were so impressed that they helped the party set up camp and even sent word up river to safeguard their passage.

Fawcett's second expedition to the Mato Grosso took place in 1907-08 in an attempt to discover the origin of the Rio Verde. Even though well-adjusted to climate and nature, Fawcett and his men more than once got close to starvation. Photo: The Library of Congress / Rolette de Montet-Guerin.

The herculean efforts Fawcett made in mapping the region in the years before World War I, however, are all too often overshadowed by his eventual disappearance. It therefore should not be forgotten that he was rewarded with the Royal Geographical Society’s Founder’s Gold Medal in 1916. The Society also saw fit to publish his article Bolivian Exploration in the March 1915 edition of its Geographical Journal. Both were considerable accolades.

Curious Creatures

As in Ceylon, Fawcett eagerly sought out archaeological remains during his expeditions in the Amazon, noting down his thoughts in a series of letters and notebooks. He was intrigued by stories he heard about the lost civilizations of South America and in one of his reports, to the Royal Geographical Society in 1910, he said: “I have met half a dozen men who swear to a glimpse of white Indians with red hair. Such communication as there has been in certain parts with the wild Indians asserts the existence of such a race with blue eyes. Plenty of people have heard of them in the interior.”

We know today that such reports were sightings of paler-skinned Indians such as the Yanomami and occasionally rare albinos. Fawcett, however, took a very different stance. He used them to bolster his belief that worldwide similarities in ancient structures, scripts and physical types indicated that early human civilisation stemmed from a single source, an ancient and long-forgotten civilisation akin to Plato’s Atlantis. He believed ardently that the remains of that civilisation lay somewhere in the green hell of the Mato Grosso (‘Great Forest’).

Fawcett never provided any drawings or photographs of the outlandish creatures he observed in the Mato Grosso. The illustration above is based on the description given in Fawcett’s diary. Photo: Jeremy Mallinson.

During his expeditions Fawcett also described creatures that at the time were unknown to science. Long studied by students of cryptozoology, they included the Mitla (a black dog-like cat about the size of a foxhound), the Doubled Nosed Andean Tiger Hound (“about the size of a terrier, it is highly valued for its acute sense of smell and ingenuity in hunting jaguars”), the blood-sucking Buichonchas cockroach, the poisonous Surucucu viper (“large yellow reptile as much as twenty feet in length”) and the Bufeo (“a mammal of the manatee species, rather human in appearance, with prominent breasts”). Some have subsequently been identified as real, whilst others branded fantastical. Particularly disturbing is Fawcett’s description of a gigantic poisonous apazauca spider, which clambered onto him as he was getting inside his sleeping bag on the banks of the Yalu River.

Considered even more fanciful by critics at the time were Fawcett’s reports of oversized creatures, including a Giant Anaconda allegedly sixty two feet long (20 metres) seen in the Rio Negro. He also claimed to have seen the tracks of “some mysterious and enormous beast” in the Madidi swamps of the Beni in Bolivia, claiming them to be possibly those of a living Diplodocus.

Lost Worlds

Very much his own man and certainly no idle dreamer, Fawcett was still a man of his time. His writings show that despite being relatively enlightened, he could never quite escape what has been called “the mental maze of race”. Additionally, during the 1890s, like many of his intellectual contemporaries, he fell under the spell of Helena Blavatsky, the Russian aristocratic mystic and founder of the so-called Theosophical Society. Blavatsky’s belief that the world was ruled by mysterious white-skinned Elders from secret locations fuelled Fawcett’s own growing interest in a lost Amazonian civilisation, perhaps once peopled by an Atlantean super-race from the Mediterranean.

In turn Fawcett influenced others, most notably the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Fawcett maintained that Doyle’s popular book The Lost World was conjured up after Doyle attended one of his lectures in 1911. During the lecture Fawcett recounted seeing the abrupt precipices of the Ricardo Franco Hills, a part of the Huanchaca Plateau in northeast Bolivia. Such a remote high plateau lies at the heart of Doyle’s book (although others have subsequently claimed that Doyle was inspired by the equally impressive Mount Roraima in the Pacaraima Mountains of Guyana). For this especially gruelling foray into uncharted wilderness Fawcett survived on palm tops and hard chonta nuts, and was repeatedly ravaged by inch-long poisonous ants.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Lost World was initially serialised in the Strand magazine. The novel is said to have later inspired Michael Crichton’s Dino Park as well as the recent Lost TV series. Photo: Strand Magazine / archives.

With all this in mind it is perhaps not surprising that Fawcett was further encouraged in his quest when the adventure story writer Sir H. Rider Haggard presented him with a curious black basalt idol. Reputed to have come from one of the lost cities in Brazil, Fawcett wrote of it, “I could think of only one way of learning the secret of the stone image, and that was by means of psychometry – a method that may evoke scorn by many people but is widely accepted by others who have managed to keep their minds free from prejudice.”

Accordingly, Fawcett took the idol to a psychometrist, who, holding the idol in a darkened room, reported seeing “a large irregularly shaped continent stretching from the north coast of Africa across to South America…then I see volcanoes in violent eruptions, flaming lava pouring down their sides, and the whole land shakes with a mighty rumbling sound…I can get no definite date of the catastrophe, but it was long prior to the rise of Egypt, and has been forgotten – except, perhaps, in myth.”

Genuine or not the psychometrist had told Fawcett exactly what he wanted to hear. He now took this to be incontrovertible proof of his belief “that amazing ruins of ancient cities – ruins incomparably older than those in Egypt – exist in the far interior of the Mato Grosso.” He went on to assert that “the connection of Atlantis with parts of what is now Brazil is not to be dismissed contemptuously, and belief in it – with or without scientific corroboration – affords explanations for many problems which otherwise are unsolved mysteries.” Whilst Fawcett would go on to find evidence for lost and hitherto unrecorded pre-Columbian societies in Amazonia in the form of causeways and pottery, all lost beneath rampant vegetation after their inhabitants had succumbed either to conquest or disease, the sweeping conclusions he drew from them were based on ill-founded dogged belief – and they would cost him dearly.

That the idol came from one of these lost South American cities Fawcett was in no doubt. Indeed, it could have hailed from one whose existence he had already read about. The evidence for it lay in the log of a Portuguese gold mining expedition from 1753 (Manuscript No. 512 in the Rio de Janeiro National Library). The expedition’s report sent by Indian runner to the Viceroy in Bahía told of an abrupt range of mountains in the previously unexplored north of Mato Grosso, on the top of which lay a vast ruined city, with the promise of gold. It also made mention of two mysterious white-skinned men, who promptly vanished into the undergrowth when the expedition approached.

Inspired by the report Fawcett now gave his own imagined city an enigmatic name – “Z” – which he claimed was “for the sake of convenience” but was more likely to protect its location from possible competitors (the British polar explorer Robert Falcon Scott had around the same time been beaten to the South Pole by his Norwegian competitor Roald Amundsen). Fawcett was now determined to locate “Z” for real – and to re-write the history books in the process.

The Quest for Z

The story of the fate of Colonel Fawcett’s last expedition is an oft-told one, being cited as the original inspiration for all classic tales of jungle adventure from Boy’s Own to Indiana Jones.

After active service in the trenches of France during the Great War, where he was promoted to lieutenant colonel for his bravery in holding his position, Fawcett returned to Brazil for another expedition in 1921, to explore the western region of Brazil. Once again Fawcett returned from the jungle alive but he had failed again to find evidence for “Z”. Now in his late 50s but still remarkably fit, he was adamant that his eighth expedition would be the one to provide the evidence he was looking for. With funding in place from a London group of financiers known as ‘The Glove’, the expedition finally came together in 1925, and consisted of Fawcett, his eldest son Jack, a would-be Hollywood actor, and Jack’s best friend Raleigh Rimmell.

Colonel Fawcett greeting local guides in the Mato Grosso in 1925. In the background (left) is Raleigh Rimmel. Photo: © Royal Geographical Society

Fawcett had always preferred small expeditions that could live off the land, believing that such a group would look less like an invasion to indigenous tribes and therefore be less likely to be attacked.

No novice in exploration, Fawcett planned the expedition meticulously yet prior to departure issued an ominous instruction to those he was leaving behind: “I don’t want rescue parties coming to look for us. It’s too risky. If with all my experience we can’t make it, there’s not much hope for others. That’s one reason why I’m not telling exactly where we’re going. Whether we get through, and emerge again, or leave our bones to rot in there, one thing’s certain. The answer to the enigma of ancient South America – and perhaps of the prehistoric world – may be found when those old cities are located and opened up to scientific research. That the cities exist, I know.”

The three men began their journey on the coast at São Paulo from where they took the train to Corumbá, a frontier town near the Bolivian border. From here a boat took them along the River Paraguay to Cuiabá, the capital of Mato Grosso, which Raleigh described as “a God forsaken hole”. This was the stepping off point for what Colonel Fawcett called “the attainment of the great purpose”.

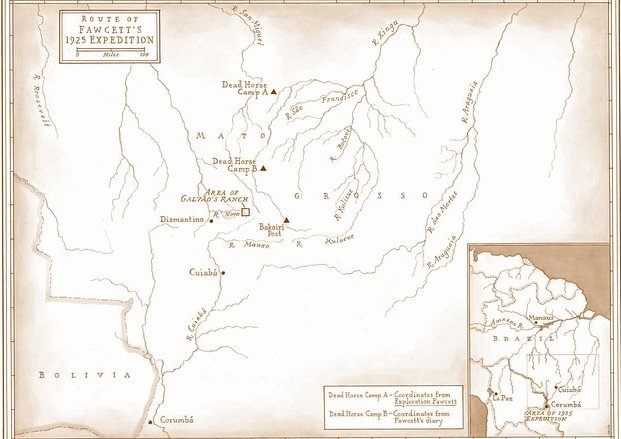

On 20th April, 1925 the party struck out northwards to the impoverished village of Bakairí Post. From here the plan was to eventually turn eastwards through the great uncharted wilderness between the Tapajós and Xingu Rivers, both south-eastern tributaries of the Amazon, and the Araguaya River. Somewhere east of the Xingu, in the mysterious Serra do Roncador (‘Snoring Mountains’), Fawcett hoped to find “Z”. Thereafter the party would cross the Rio São Francisco into Bahía state to explore the ruined city described in the 1753 manuscript, and finish up on the coast at the capital, Salvador.

On May 29th, 1925, Fawcett sent a message to his wife indicating that the expedition was crossing the Upper Xingu, and was now poised to enter territory hitherto unexplored by Europeans. “Our two guides go back from here,” he wrote “they are more and more nervous as we push further into the Indian country.” Carrying only minimal provisions (as well as Rider Haggard’s curious idol) Fawcett reassured his wife with these words: “You need have no fear of failure…”. The three members of the Fawcett expedition then disappeared into the jungle never to be heard from again.

The Hunt for Colonel Fawcett

Despite the Colonel’s wishes, more than a dozen expeditions subsequently set out to discover the fate of the lost expedition. Allegedly claiming the lives of up to a hundred men, they generated little useful evidence of Fawcett’s fate. For some, ‘looking for Fawcett’ became an obsession, even a profession of sorts, offering exactly the type of adventure Fawcett himself found so addictive. And there was commercial gain to be had, too, whether in the form of book deals and newspaper articles for those leading rescue parties, or rewards for those Indians willing to reveal evidence, however spurious, of the lost expedition. Over time finding evidence of Fawcett became a more lucrative business than finding his fabulous lost city.

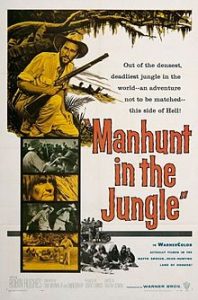

Movie poster for Manhunt in the Jungle (1958) starring Robin Hughes as Colonel Fawcett. Photo: Warner Bros.

The Fawcett expedition was not expected back until 1927 but when it failed to reappear the rumours started flying. Had the Colonel lost his mind? Had he been held captive against his wishes by cannibals? Or perhaps he had decided to stay amongst a tribe of Indians, who now saw him as their chief? Against this backdrop the first major rescue party set out a year later in earnest, led by Commander George Miller Dyott, a man familiar with the Brazilian hinterland. Despite being dubbed “The Suicide Club” it attracted a huge number of volunteers looking for adventure. Dyott picked up Fawcett’s trail in the village of Bakairí Post, and followed it across the wilderness of Central Brazil and into the Amazon forest but was eventually driven back by hostile Indians and lack of supplies. From what he could glean from the Kalapolo tribe of the Upper Xingu, and the discovery of a brass plate carrying the name of the company that had supplied Fawcett’s gear around the neck of an Indian, the Colonel and the others had most likely been murdered. These sketchy findings were detailed in Dyott’s extravagantly-titled book Man Hunting in the Jungle – Being the Story of a Search for Three Explorers Lost in the Brazilian Wilds (1930), which which received the silver screen treatment in 1958 as Manhunt in the Jungle.

Men of the Kalapalo tribe photographed by a missionary in 1937. Photo: © Royal Geographical Society

A very different story emerged from the jungle four years later courtesy of a Swiss traveller called Stefan Rattin. He had travelled into Mato Grosso along the Rio Arinos, where he claimed to have met an elderly white man with a long beard held captive by the Indians. The man allegedly revealed himself as Colonel Fawcett and showed him a signet ring, which he asked Rattin to report upon his return to São Paulo. Although doubted by many, Fawcett’s wife Nina said she recognised immediately the description of the ring, stirring up enough interest for further rescue expeditions to be mounted.

They included an English actor called Albert de Winton, who ended up clubbed to death in his canoe, a female anthropologist who came out of the jungle alive only to succumb later to an infection, and another anthropologist who hanged himself from a tree. One of the more successful expeditions was notable for the presence of Peter Fleming, brother of James Bond creator Ian Fleming, who in April 1932 replied to an advertisement in the personal columns of The Times: “Exploring and sporting expedition under experienced guidance leaving England June to explore rivers Central Brazil, if possible ascertain fate Colonel Fawcett; abundant game, big and small; exceptional fishing; ROOM TWO MORE GUNS.” With Fleming onboard as official correspondent, the expedition organised by Robert Churchward embarked for São Paulo. From there it travelled overland to the Araguaya River and then headed for the Upper Xingu and ‘Dead Horse Camp’, the last reported position of the Fawcett expedition (the camp was so-named because Fawcett had shot a sick pack horse here on an earlier expedition). Riven by internal disagreements from the start, however, Fleming soon formed a breakaway party to look for Fawcett independently. Both made slow progress for several days before finally admitting defeat.

The return to civilization became a closely-fought race between the two parties, the prize being the privilege of reporting home first, and gaining the upper hand in the inevitable squabbles over blame, squandered finances and book contracts. Fleming’s party narrowly won, returning to England in November 1932. His tale of the fiasco, Brazilian Adventure (1934), is now considered a minor classic of travel writing, in which Fleming, on the subject of Fawcett, remarked that “enough legend has grown up around the subject to form a new and separate branch of folk-lore”.

Peter Fleming, the older brother of James Bond creator Ian Fleming, worked as special correspondent for The Times. His Brazilian Adventure relates one of many attempts to solve the Fawcett mystery. Photo: Harropian Books/Charles Scribner’s Sons.

By contrast, Robert Churchward’s wonderfully-titled Wilderness of Fools – An Account of the Adventures in Search of Lieut.-Colonel P. H. Fawcett (1936) vanished as mysteriously as its subject.

Fawcett Fever

Except for the brass name plate found in 1928 and a theodolite compass recovered in 1933 (probably jettisoned during an earlier expedition), nothing tangible had ever emerged from the jungle since the Colonel’s disappearance in 1925. Most likely the expedition had been murdered either by hostile Indians (perhaps the Xavante, Suyás or Kayapós, whose territory Fawcett was unwisely entering) or else friendlier ones (the Kalapolo, who were probably the last to see the men alive and subsequently reported that the two younger members were lame). Alternatively they might have been murdered for their rifles by renegade soldiers roaming the forest in the wake of a recent revolution in the area. Disease or some accident might also have been to blame, although starvation seems less likely given Fawcett’s longstanding experience of living off the land. It is also highly unlikely given Fawcett’s experience that the expedition got lost.

Fawcett’s son Jack accompanied his father on his last great expedition to the Mato Grosso in 1925. Photo: © Royal Geographical Society

If the Kalapolo were indeed the culprits perhaps they killed the three men to prevent them from entering the territory of a more aggressive tribe, which might otherwise exact revenge on the Kalapolo? The story came to a head in 1948 when the Xingu-Roncador Expedition was laying out airfields in the territory of the Kalapolo Indians. They won the confidence of Kalapolo Chief Ixarari, who claimed to have killed Fawcett and his two companions after Jack Fawcett had fathered a child with a local girl. This bolstered rumours circulating since the mid-1930s of a young pale-faced Indian seen in the area (yet another expedition had recently returned with a terrified albino boy named Dulipé, who its leader insisted was Jack’s son). The chief went on to say that the three bodies were then weighted with stones and thrown into the Tanguro River. Fearing detection, however, the bodies were retrieved and left on the bank to be scavenged, after which the bones were dispersed.

Conversely, according to the Brazilian activist for indigenous peoples, Orlando Villas Bôas, the Kalapolo murdered the men because they had run out of gifts to encourage the Indians to continue helping them, the younger members being thrown in the river and the colonel buried, out of respect. In 1951 Villas Bôas even produced a skeleton said to be that of Fawcett but subsequent bone analysis disproved his claim. By bringing closure to the story albeit spuriously Villas Bôas wanted to protect the Indians from further external intrusions.

With so little to go on Fawcett rumour-mongering rolled on unabated. In the late 1940s, for example, a New Zealand schoolteacher by the name of Hugh McCarthy quit his job and went in search of Fawcett’s lost city of gold using carrier pigeons to relay news of his progress. His last post detailed his imminent death and also made tantalising reference to an earlier communication giving the exact location of “Z”. The pigeon carrying that particular letter never arrived and McCarthy vanished forever.

Around the same time author Harold T. Wilkins in his book Secret Cities of Old South America (1950) related how an anonymous informant had told him that a German anthropologist by the name of Ehrmann had seen Fawcett’s shrunken head in a village in the Upper Xingu in 1932. Apparently the Colonel had died defending his son Jack, who had broken some sort of tribal taboo. So the rumours kept coming.

Into the story now steps Fawcett’s son, Brian. Too young to have participated in his father’s fateful expedition, he had made a life for himself as a draughtsman on the Peruvian railways. To set the record straight once and for all he compiled his father’s reports and letters into a book (according to Fawcett, the manuscript of his own planned book to be called Travel and Mystery in South America was lost in 1924, whilst doing the rounds of potential American publishers). The result was the bestselling Exploration Fawcett (1953).

A bestseller in the making: the letters and reports of Colonel Fawcett as assembled by his youngest son, Brian, in the book Exploration Fawcett. The image shows the cover of the first edition published in 1953. Photo: eBay.com

Brian’s thrilling and highly readable re-telling of his father’s jungle adventures is peppered with his own expertly drawn maps and illustrations. Yet still no answer was provided as to the fate of the expedition: “Up to the time of writing these words the fate of my father and the two others is as much of a mystery as it ever was. Is it possible that the riddle may never be solved?”

Colonel Fawcett’s interest in the occult also ensured a steady flow of more esoteric accounts, chief amongst which was Geraldine Dorothy Cummins’ The Fate of Colonel Fawcett: A Narrative of His last Expedition (1955), based on her supposed psychic contacts with the Colonel up until 1948, when she claims he reported his own death to her. As late as 1934 Fawcett’s wife Nina also claimed to have received telepathic messages from her husband, and the family are said to have employed a medium to analyse a scarf once worn by the colonel: in a trance the medium clearly saw the party murdered and their bodies dumped in a lake.

Ruins in the Sky

Prompted by the discovery of the alleged skeleton of his father by Villas Bôas, Brian Fawcett embarked on two of his own expeditions into the Mato Grosso, in an attempt to solve the mystery for himself. He bore a striking physical resemblance to his father and was a tough traveller in his own right. The result was his own book called Ruins in the Sky (1958).

Although once again no answer was given to the fate of his father, Brian did manage to throw some much-needed light on the lost city of “Z”. Using the reported sighting of a lost city by one Colonel Francisco Barros Fournier in the Review of the American Geographical Society for 1938, he was able to fly over an area six kilometres west of Pedra da Baliza in the Brazilian state of Goiás, which is sandwiched between Mato Grosso and Bahía. The reported walls and towers were nothing more than a naturally eroded series of ridges, exactly like those of the Sete Cidades, a group of seven alleged ‘lost cities’ Brian visited in the far north of Piauí state. Might “Z” have been nothing more than a geological formation glimpsed fleetingly by the Colonel on one of his expeditions?

In his book Brian also wrote sceptically of reports that his father and brother Jack were living in a secret underground city from where the world was ruled by Madame Blavatsky’s superior Elders, a fantastical notion that still helps sell esoteric books to this day.

Contemporary news coverage upon the release of Brian Fawcett’s Exploration Fawcett. Photo: fawcettsamazonia.co.uk

Brian Fawcett’s motives for taking up the story after such a long time are unclear. A very competent writer and an excellent illustrator, perhaps he thought it high time that he shared a little of the excitement and the financial rewards that his father’s legend continued to generate. Whilst speaking respectfully of his father’s achievements, he tellingly recalls being in his presence as “uncomfortable apprehension, like being in the company of a well disposed but uncertain schoolmaster.” And his dedication of Ruins in the Sky to his wife Ruth, “the one who was not left behind”, is certainly a pointed remark on his father’s apparent abandonment of Nina over so many years of adventuring.

Of his father’s historical professionalism he also casts some doubt, claiming to have no idea “how much was based on research, how much on personal knowledge, and how much on the babblings of clairvoyants.” Compared with his older brother Jack, apparently his father’s favourite, Brian perhaps felt less important. Was good quality writing (and a little debunking) perhaps a way of getting even with them by achieving something neither of them were now able to do? Or was there something more sinister at play?

The Colonel Comes of Age

Fast forward forty years and the Fawcett story was in the news once again. In 1996 a television expedition put together by a Brazilian banker, James Lynch, set off into the Mato Grosso to search for any remaining traces of the Fawcett party. It didn’t get far. Kalapolo Indians stopped the group and held them hostage for several days, only releasing them after confiscating $30,000 worth of equipment.

Rather more successful was a one-man expedition undertaken two years later by maverick adventurer and anthropologist Benedict Allen, who filmed his progress as part of the BBC’s Video Diaries series. In exchange for an outboard motor he was told by the then chief of the Kalapolo that his tribe had nothing to do with the expedition’s demise, and that Fawcett and his two companions died four or five days east of Kalapolo territory, at the hands of the aggressive Iaruna tribe. Allen was also told that the Villa Bôas skeleton was certainly not that of Fawcett but rather that of the chief’s own grandfather.

With the start of a new millennium the Fawcett legend came of age with probably the most extraordinary twist yet in its very long tale. In 2002 a Czech theatre director called Misha Williams informed the press that the Fawcett family had agreed to grant him exclusive access to their archives. What he uncovered was a revelation. Brian Fawcett, it seems, in collusion with the rest of the Fawcett family had deliberately obscured his father’s tracks in the book Exploration Fawcett by including false coordinates for Fawcett’s last known position (Dead Horse Camp). The reason for this, Williams claimed, was that the family had always known that Fawcett never intended to return and instead intended to set up a Utopian commune deep in the jungle, part of what he called his “Great Scheme”. And why not? After all, “The English go native very easily,” the Colonel once wrote, “there is no disgrace in it.”

This new society, according to the secret papers, would be founded on Madam Blavatsky’s Theosophical principles, which the colonel had been busy perfecting over the years, with the help of a spirit entity he called “M”. The reason for the Fawcett family’s reluctance to divulge the truth, Williams contended, was that the world was just not ready for such sensational news. Just as soon as they heard from him, the remaining Fawcett family members would pack their bags and join the Colonel and Jack.

If Williams’ claims are true, it is little wonder that the missing expedition was never located since the rescue parties had been looking for Dead Horse Camp in the wrong place. Perhaps Fawcett had in fact found exactly what he was looking for and was just waiting for a chance to get word back to his family? Cynics might say that such revelations merely provided useful publicity for Williams, who at the time was promoting a play he had written about Fawcett called AmaZonia. But in yet another twist to the tale, a documentary team pursuing the Fawcett trail later tracked down Rolette de Montet-Guerrin, Fawcett’s granddaughter. She confirmed the coordinates’ cover-up and gave her blessing for the team to pursue the correct ones. Armed with Fawcett’s signet ring, which had mysteriously turned up in a Brazilian market, they finally identified the real Dead Horse Camp. The result is a marvellous piece of documentary film making entitled Lost in the Amazon, which has been screened on PBS as part of the Emmy Award-nominated Secrets of the Dead series.

Front cover of David Grann’s The Lost City of Z, the latest book to try to unravel the mystery of Colonel Fawcett’s disappearance in the Amazon. Photo: DoubleDay Publishing

In 2009 Fawcett fever returned once again with the publication of The Lost City of Z by David Grann. A respected writer for The New Yorker, Grann admits early on in his book to being more adept at writing than exploring and goes on to describe in humorous detail his own 2005 expedition into the Amazon Jungle. His conclusions about “Z” on the other hand are deadly serious.

Grann reports that the Kalapalo still recall Fawcett in their oral history since the Colonel and his companions were some of the first white men the tribe had ever encountered. The book’s greatest revelation, however, is that a monumental civilization did actually once exist near to where Fawcett was looking. Its remains, however, which were occupied between 800 and 1600 AD, are not stone but rather earthen. Consisting of massive causeways, ditches and platforms, they are in the process of being revealed by archaeologist Michael Heckenberger, Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Florida. Far from being a ‘counterfeit paradise’, as had long been claimed, Heckenberger is demonstrating that the Amazon rain forest once supported civilizations as complex and populous as those of the Inca and the Maya. This explains the great cities reported by the Spanish conquistadors in their relentless search for El Dorado but which had been swallowed up by the forest once their inhabitants had succumbed to European diseases. Colonel Fawcett’s lost city of “Z” had been there all the time.

Inevitably given the enduring nature of the Fawcett story, the rights to Grann’s book were recently sold to Paramount Pictures, with none other than Brad Pitt slated to star as Fawcett. When he stepped aside from the project due to other commitments, followed quickly by his successor Benedict Cumberbatch, Fawcett’s well-worn boots were filled by up-and-coming actor Charlie Hunnam, ably supported by Twilight star Robert Pattinson and model-turned-actress Sienna Miller.

Clearly only the big screen – and big stars – can do justice to the larger-than-life reputation of Colonel Fawcett. Share in the adventure when The Lost City of Z comes to a cinema near you – and watch out for those seven-foot-long arrows.

Leave a Reply