Three Narratives Explaining Why The Capitalist Mode of Production Is A European Invention

Introducing three prominent scholars and their theories on why capitalism emerged first in Europe – and nowhere else in the world.

Reading time: 20 minutes

Europe is something else. For the last 500 years the tiny continent has seen historical, economical and cultural development second to none in recorded history. Be it scientific discoveries, a blossoming of arts or the mastery of nature, the last half-millenium of European history is unrivaled in regard to the progress of man.

Why is that? What made Europe the cradle of such a favorable development while other parts of the world seem left behind? For a start, it is helpful to put Europe into perspective. One example that makes the point is that Europe never lost contact with its heritage, namely that of the Ancient Greek and Roman Empires. Europe draws from the cultural foundation on which it stands, and some will even say that the advanced Europe of today is nothing but an elongated version of its 2000-year-old essence.

Is that it? Does history make the case, i.e. Europe as a spoiled child with a privileged upbringing? A short-lived argument in any case, we would like to think. Another, more striking explanation we will look into comes from a more ‘down-to-earth’-perspective – in the very literal meaning of the term: One of the most life-altering ‘inventions’ of mankind, namely that of agriculture, came to life basically everywhere else in the world before it ever became prominent in Europe. With Europe put into perspective we are gaining a sharper view on our core question: why is it that only Europe brought about modern day capitalism, with all its up and downsides?

Europe Embraces The Ancient World: The Renaissance

Europe – unrivaled? Going back in time it there have been other ages shaping the world with similar profoundness. Which are those ages?

Take, for instance, the already mentioned Ancient World. In countless aspects Ancient Greece served – and still serves – as a never-ending source for European

Raffael’s The School of Athens, located on the walls of the Apostolic Palace, the residency of the pope, is a splendid image of the newfound interest in Ancient Greece during the Renaissance. The painting portrays the brightest minds of several epochs all gathered together on the Ancient Greek agora, the ancient center square which served as a gathering point for philosophers. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons

inspiration. When Europeans embraced the re-emerging interest in ancient philosophy, arts and literature during the 15th and 16th century, they labelled the phenomenon a rebirth (‘Renaissance’) of Ancient times.

Europe As A Latebloomer: The Neolithic Revolution

Going back further in time, as it turns out, there are even more striking changes in world history that were not inherently European. The Neolithic Revolution, for one, which was the transition of man from being hunter-gatherers to settling down and engaging in agriculture and animal breeding, took place in three different regions of the world and independently from each other – none of these regions was Europe.

Coined the term of the Neolithic Revolution: Vere Gordon Childe | Photo: Greatarchaeology.com

The Middle East (9000 b.c.), Central America (3000-2000 b.c.) as well as Southern China (7000 b.c.) were the places where agriculture first came about. The newly invented social formation of living in steady housing with exclusively self-enticed means of survival only got to Europe later in time. Mainly, agriculture spread from East to West via the Mediterranean Sea or via expansion of the Linear Pottery culture along the Danube River, as renowned Australian-British archaeologist V. Gordon Childe had pointed out. In regard to the mastery of nature our Western Europe of today has to be seen not as a pioneer, but rather as a latecomer. A view on things that receives reinforcement, if you look at history from a scope that goes beyond the past 500 years..

The One Remarkable Thing Only To Emerge In Europe

What is left? One may indeed ask what makes for Europe’s alleged exclusiveness when so many of the great achievements in world history – if not the majority of them – at some point have already emerged elsewhere in the world. A commonplace in this regard is the fact that the great invention of printing with movable letters, to be claimed by German

inventor Johannes Gutenberg in the year 1440, in fact has been around since the year 990 A.D. Originally invented in China, even printing with movable letters has seen an earlier birth than when it was ‘re-‘ invented with movable metal-made letters in the heart of Europe.

So what really is left? There must be something as there has to be a reason why English has become the world’s leading language while Chinese, even though the Chinese Han Dynasty has been the world’s inventive power house for four centuries (207 b.c to 220 A.D.), hardly ever spread outside of the Chinese mainland. What is the one cultural aspect that sets Europe apart from all of its predecessors in terms of science, culture and development?

One pathway to an answer leads back to the already mentioned agriculture. The one thing that the Ancient World and ancient China had in common was that both relied on feudal labor for their economic survival.

While feudal labor in regard to Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome can simply be translated as slave labor, Ancient China saw a slight difference in its particular mode of production. The asiatic mode of production was not so much about a personal bond – a type of social cohesion which in Europe appeared in the literal meaning of the term as bondage – between aristocrats and peasants, but rather about the peasants’ obligation to pay tribute to a rather impersonal class of rulers. German sociologist and historian Karl August Wittfogel further developed Karl Marx’ concept of the asiatic mode of production and stressed that in China peasants were formally free and argued with aristocrats over the amount of taxes they had to pay.

The mentioning of slave labor as well as feudal labor, however, sets the stage for the discussion of the distinctively modern type of labor, namely free labor. The one remarkable thing only to emerge in Europe is a specific formation of human labor that with the full spectrum of its economic connotations has found its way into collective memory under the term of capitalism.

The Intellectual Point Of Departure: Feudalist Society

In Europe peasants were undeniably attached to the land they worked and lived on. This went as far as to the well-known proverb of cuius regio, eius religio: if a prince lost some of his land due to war, if he sold it or if he simply converted to Protestantism, the peasants living and working on the land he owned were to switch religions as well: whose land, his religion. On the other hand, a prince was obliged to ‘care’ for his subjects in the sense of protecting them from outside threats as well as ensuring he would always have control over sufficient amounts of fertile land.

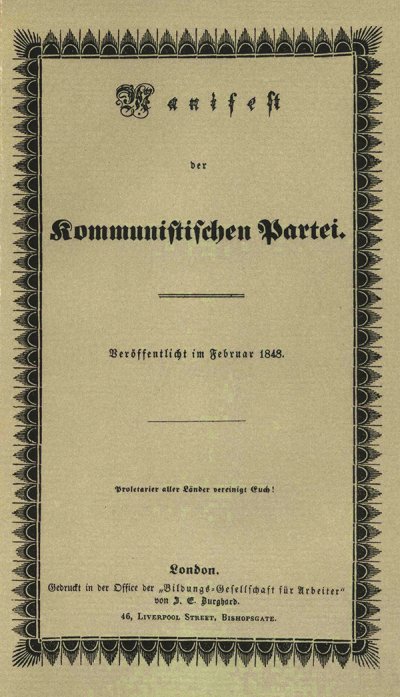

It is this feudal bond between peasant and ruler – a mere social transposition of what in a more narrow sense would file as pimping – that makes for a major target of Marx’ argumentation. Most prominently in his brilliant essay of 1848, the Communist Manifesto which he co-authored together with his lifetime friend Friedrich Engels, Marx states that one of the ‘first victims’ of capitalism was the destruction of the feudal bond. Who was Marx and what was his main argument in his particular explanation for the rise of capitalism?

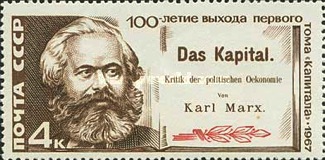

Material Production: Karl Heinrich Marx

*1818 in Trier, Germany | † 1883 in London, England

Born into a Jewish family that later converted to Protestantism Karl Marx grew up in the Rhineland, at his time one of the most progressive regions of the not-yet-unified German nation.

Picking up studies in law which then served as the overall concept for what today would be considered humanites – or Gesellschaftswissenschaften as would be the German term – Marx completed his studies with a dissertation in philosophy on the Differences Between Democritean And Epicurean philosophy of Nature. Besides being heavily subsidized by Friendrich Engels whose father was a wealthy factory owner, Marx technically worked as a newspaper editor and correspondent throughout his life.

After the first newspaper Marx worked for had been shut down down due to the Karlsbader Beschlüsse – censorship edicts that were issued to reestablish Europe’s aristocracy-based order after the bourgeois revolution of 1848 failed – Marx emigrated first to France, then to Belgium and ultimately to London where he died at the age of 75.

A Communist avant la lettre, his writing soon turned from radical democratic to anti-bourgeois. His early works culminated in publications such as the Holy Family (1845),

a radical critique of the disciples of the late philosopher Hegel, the Poverty of Philosophy (1847), a rebuttal to the Philosophy of Poverty (1846) by French philosopher Pierre Proudhon whom Marx accused of having a limited understanding of Hegel, to the revolutionary Communist Manifesto of 1848.

It is in the brief, but brilliantly written Communist Manifesto that Marx discusses the emergence of capitalism from a distinctively European point of view. The opening line stating that that “Europe is haunted, haunted by the spectre of Communism”, sets the frame for the following analysis, i.e. a predominantly European frame, and has become somewhat of a household phrase in academia.

Marx On Europe: The Communist Manifesto

In the Communist Manifesto all of history is discussed with Europe as the center stage. Side-views to other historical scenarios are simply left out.

For Marx, it was in Europe that the three Estates of the Tennis Court Oath have merged into two, the Bourgeoisie and the Proletariat. All occasions that would hint at the near end of the Bourgeoisie, like pauperism, Marx witnessed with his bare eyes in Europe.

Guerrilla warfare, indigenous movements or other working class-related movements like you would find them today in Colombia, Mexico or Papua New Guinea was no concept Marx ever thought of. A fact that has to be held against him: all movements only remotely resembling a proletarian revolution have had peasants as their social carrier — and not urban factory workers like Marx had thought.

The history of man, for Marx, is the history of man’s society, and the ‘final battle’, the historical chance for man to step up and “consciously make his own history”, as he put it, was something that — if it happened at all — would implicitly happen in Europe.

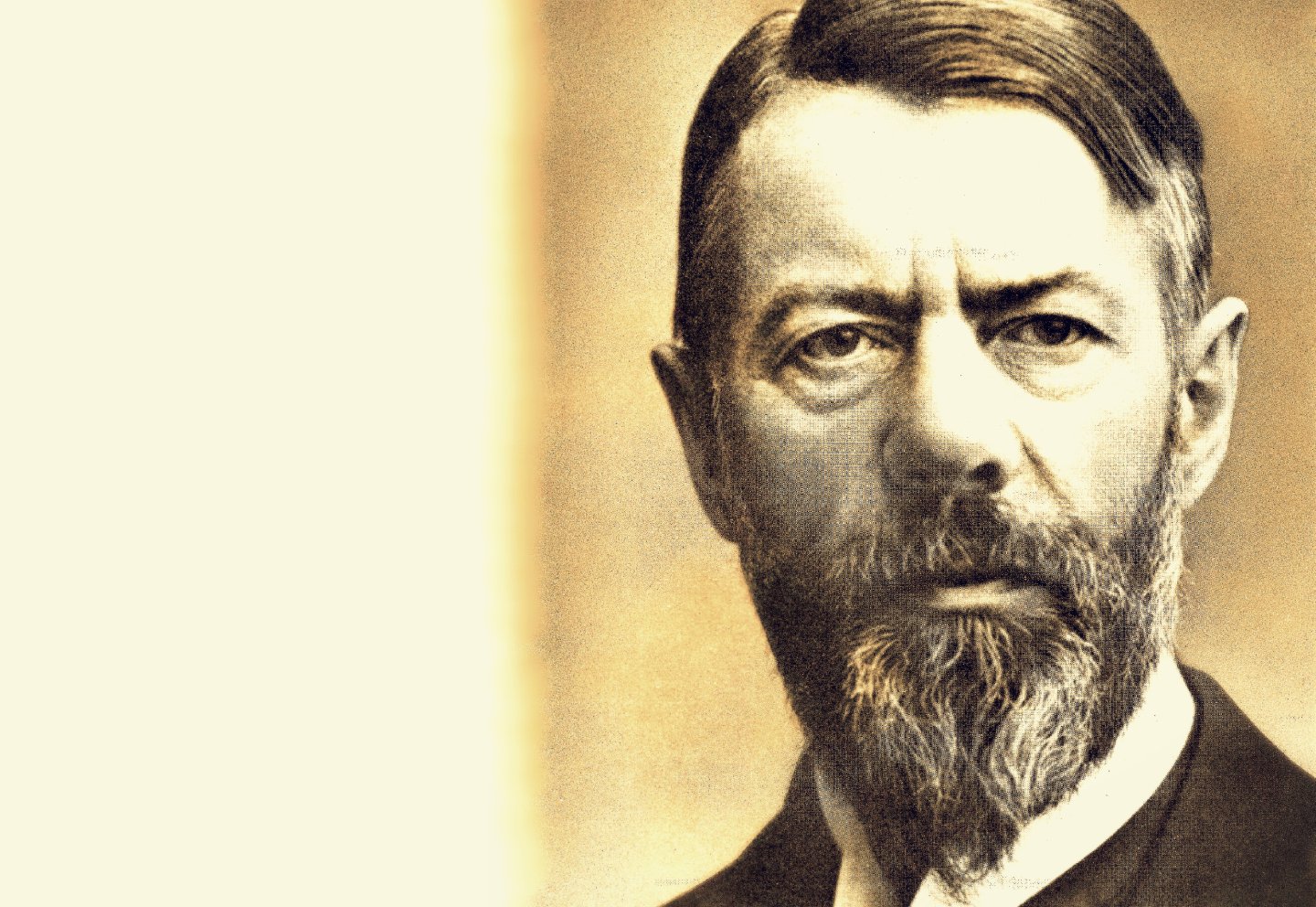

At the beginning of his famous “Protestant Ethics” Max Weber (below) would later refer to himself as a “son” of the modern European cultural realm – Karl Marx has done the same, only he did it implicitly.

Marx On The Origin Of Capitalism: Das Kapital

How did it all begin? What are the fundamentals of a never seen before productivity? Of the revolutionizing of feudal-based modes of production to the extent that the “bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society,” as the Manifesto says?

At the very beginning of capitalist development stands a certain historical act. Marx describes it in a chapter of 1871’s Das Kapital which is titled The So-Called Original Accumulation. Here, he makes the point that other Economists, Marx is referring to Adam Smith, are erring when they proclaim an organized caste of ambitious entrepreneurs as the origin of capital. In fact, states Marx, there has never been class of frugal entrepreneurs who through their economical lifestyle alone saved up so much resources that society would split into the two classes of capitalists on the one side, and the proletariat on the other.

Russian stamp issued to the 100th anniversary of Das Kapital | Photo: stampworld.com

The real reason how such a division came about, according to Marx? — Brutal physical violence. The transition of a feudal society with peasants living on the land that sustained them to an industrialized one where peasants have become workers finds its root in violence and displacement. Displacing people from their land and thus parting them from their means of production has been a century-long, violent process.

These newly ‘displaced persons’ would now depend on employment. They have become proletarians, i.e. those who own nothing but their proles, that is their offspring. Marx hence calls the Original Accumulation an original expropriation.

The outcome of throwing people off their land and into workhouses and poor houses? Just as so vividly portrayed in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist it was wage laborers that now made up for the majority of the population. Wage laborers who were, as Marx put it, free to a double-extent: with the feudal bond gone for good they gained all civil rights they had been withheld thus far., while at the same time they were free of any means of production: they had become have-nots. Human labor now was a commodity, freely to be allocated through the market principle alone.

While the Communist Manifesto is in awe to the productivity that is set free once human labor is organized in the capitalist mode of production, way Marx does not fail to stress the pathological aspects of such development. Labor can no longer be an expression of human craftsmanship or artisanship, but has grown to be something that will dictate and subjugate man. As ‘stored labor or even ‘dead labor’ (Marx) capital was eventually meant to become a social actor itself, actively mutilating the development of man’s full potential.

In regard to Europe, Marx is an implicit euro-centrist. Witnessing first hand what historians would later refer to as industrialization Marx had no real inclination – nor any real interest – to highlight Europe’s role in the rise of capitalism. Another European scholar who had a rather differing view on the role of Europe was German philosopher Max Weber.

Religion: Max Weber

*1864 in Erfurt, Germany | † 1920 in Munich, Germany

The German historian, religious historian, sociologist and politician Max Weber is often described as the ‘Bourgeois antipode’ to revolutionary Marx. An assertion that is both true – and utterly false at the same time.

It is true as Weber comes from an entirely different academic background: While Marx drew heavily from French materialism where matter is the only real entity, an assertion that Marx expanded when he declared man’s society the actual human ‘matter’ that in history had been transforming itself through revolutionary class struggles, Max Weber stands in the tradition of Neo-Kantism where not mindless matter, but an active, ultimately reason-

inspired relation to the world was the focus of analysis. Therefore, simply considering Weber an intellectual opponent to Marx does not do him justice. Even though from a completely different academic angle Weber analyses capitalism from a subjective point of a view, focussing on the internal motivation that led to the rational working regime we call capitalism. In that sense, it would be false to put Weber into mere opposition to Marx as Weber was basically picking up on a blind spot in Marx’s analysis: the so-called subjective factor in the development and, almost more importantly, the sustainment of capitalism.

Weber And Marx’ Heritage: Opposition And Revival

Indeed, a subject-based outlook on capitalism was something Marx ultimately considered useless. Already in 1845, in the German Ideology, an anthology which Marx co-authored together with his fellow in exile, Friedrich Engels in Paris and that was only published in 1932, he found clear words as what to think of any society’s self-attribution:

Whilst in ordinary life every shopkeeper is very well able to distinguish between what somebody professes to be and what he really is, our historians have not yet won even this trivial insight. They take every epoch at its word and believe that everything it says and imagines about itself is true.

If one wanted to analyze capitalism by referring to what those time-bound individuals of any epoch had to say, write and criticize about themselves one would always end up in a fallacy. For Marx, analyzing the objective aspects of society, that is the means and relations of production which could not be altered by interpretation or dogma, was key to an unfiltered understanding.

Max Weber, however, sees things differently. While he surely does not fall for any positivist fallacy, either, Weber focuses on the inner strivings that led certain social groups to develop different morally based approaches to labor. Far from proclaiming a mere history of big men or losing oneself in psychological assumptions Weber found a way to establish a sociologically-induced explanation of capitalism. For Weber, any economic regime would ultimately comes down to a certain work ethic. This work ethic, says Weber, is something that in non-secular societies has been profoundly, if not exclusively, been shaped by religious beliefs.

Weber On Europe AND Capitalism: The Protestant Ethic And The Spirit Of Capitalism

In any pre-modern society economic action is shaped by religious beliefs to an extent that is simply incomprehensible to us today

As we shall see, discussing Europe and Capitalism as two separate entities in Weber can hardly be justified.

Why is that? As the quote above shows Weber states an intrinsic relation between religion and economy, and that even more so for traditional societies. What at first sight seems rather unusual, especially if you look at it from secular point of view, was anything but implausible in non-secular, traditional societies.

Here, most values, including those regarding economic action, were shaped by religious conviction. A fact that today is still alive in orthodox Jewish communities all over the world where even lighting a match on the Holy Shabbat is prohibited. It is this empathic approach to religion and economic behavior that serves as the baseline of Weber’s research: ny world religion, any sect or any religious splinter group will always feature a religiously sanctioned approach to the material world.

The Protestant Ethic And The Spirit Of Capitalism

It is this analysis of work ethics that Weber first introduced in his groundbreaking study The Protestant Ethic And The Spirit Of Capitalism. Published in 1904/05 the study was heavily influenced by a trip through the United States that Weber had undertaken in the previous year. Visiting the numerous Protestant sects in the New World and experiencing first hand the unique blend of a pious yet so industrious lifestyle only seemed to enforce Weber’s thesis, namely that there is an incoherent correlation between Capitalism and Protestantism.

This very notion, today widely referred to as the Weber thesis, also defines Weber’s perception of Europe. Of course, Weber’s Protestant Ethic is well-known for stating that “(…) Capitalism has existed in China, India, Babylon, the Ancient World and the Mid-Ages”. But what may look striking at first is immediately put into perspective. Weber adds right away that while capitalism may have existed throughout all ages, the type of capitalism one would encounter in Ancient India and Ancient China in fact was about either hoarding riches in the proverbial treasure box or they were linked to conquest and overpowering. Once gained through violence, riches were then wastefully spent with no remorse. A fact that led Weber to labeling these rudimentary types of capitalist behavior “adventure capitalism”, i.e. the type of behavior you would find in warlords, Conquistadores or audacious businessmen like Jakob Fugger.

It was a certain ethos, a certain subjective work ethic – the Protestant – one which made ascetics, that is: the saving, investing and lending of funds a noble and heavenly task. A task that would have nothing to do with conquest or excess, but everything with silent steadiness. And that particular work ethic – or that particular religion, if you will – only came about in Europe – and nowhere else before or after. Only European Protestantism developed a work ethic where economic action and the prospect of salvation merged into a symbiosis. In fact, the earthly economic performance in early protestantism is seen as the indicator for a possible salvation. An understanding that the Gospel of Matthew puts into the phrase of “By their fruit you will recognize them” (Matthew 7:16).

Breaking Economic Mono-Causality

The Weber Thesis was a landmark attempt to pushing the then still dominant economic interpretation of history, Marx’ Historical Materialism, out of the academic discourse. During the first congress of the German Association of Sociology in 1910 Weber found clear words for his own understanding of which were the active powers in history – and which were not: “Referring to ‘The Economical’, in whatever sense, as something ultimate in a succession of causes, this very notion in my opinion is academically done in its entirety.”

Furthermore, by referring to religion, i.e. ideas not as a driving force, but as a contributor to the course of history, Weber paved the way for a discourse that would acknowledge the autonomy of the cultural sphere, thus setting the stage for thinkers like Pierre Bourdieu, Ernst Cassirer and many others.

Physiology and Geography: Jared Diamond

*1937 in Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Drawing a continuous line from the ‘Materialist’ Marx to the ‘Idealist’ Weber to the New England scholar and professor of geography Jared Diamond seems an impossible endeavor.

A physiologist by trade Diamond does not focus on mind- and soulless matter, nor does he try to bring a sociological version of moral philosophy into the equation. As a physiologist it is living organisms that make up for the center of his academic interest. This being said, could there be any wider gap to bridge than that between organisms that by their nature have no concept of economy and an industrial mode of production, i.e. capitalism?

Things get a lot clearer once you dive into the first chapter of Diamonds well-received book of 1997 titled Guns Germs and Steel. In the first chapter of the book that, among others rewards, in 1998 won him the Pulitzer Prize, Diamond lays out the very question he seeks to answer with his monograph.

Diamond On Europe: An Advantageous Distribution Of Organisms

The very question answered in Guns, Germs And Steel is one that Jared Diamond named ‘Yali’s Question’: while doing research in Papua New Guinea Diamond was approached by a local politician who asked him for the reason why Diamond’s part of the world had so much in wealth, infrastructure and resources, a conglomerate of opportunity for which New Guineans adopted the Spanish/American term cargo, while his part of the world had so little.

Diamond’s answer to Yali’s Question goes far beyond the 500 years that make up for the time frame for the analyses of Marx and Weber. In fact, the genuine and multidisciplinary way in which Diamond fruitfully combines

physiology and geography allows to reconnect with the already mentioned Neolithic Revolution and the invention of agriculture: It is one of Diamond’s great merits to have delivered a valid explanation as to why Western Eurasia – in regard to Europe Diamond mostly argues from a geographical point of view where Asia and Europe are considered part of the same landmass, Eurasia – was the one continent to give birth to a farm-based way of life.

What is that explanation about? If one wanted to comprehend the settlement of man from a purely physiologist perspective then the whole century-long process can be described as the domestication of both vegetal and animal organisms. This definition of agriculture relates to Europe in the specific sense that Europe was the only continent equipped with, if you will, the genetic makeup in animals and plants that would allow for a successful domestication in the first place.

Take the continents of Australia and Oceania, for instance. Due to classic natural selection this part of the world is not inhabited by a single animal apt for pulling a plow or nurturing man with eggs and milk or even keeping man warm with its wool. Not a single native mammal of such qualities is found on the whole continent of Australia The same is true for the continent of Africa where there are animals that would make excellent working animals (elephant, zebra). Yet the elephant and the zebra, like many other African species, both share the character trait that they are simply indomitable and/or will die in a captive state. The same would also be true for South America with the Llama and Alpaca being the only larger mammals of the whole continent, providing for nothing more than their mere wool.

Compare to that the relative ease and fruitfulness with which the Eurasian horse, sheep, goat, cow and pig have been domesticated and you will begin to fathom how much influence the mere distribution of organisms has had on the economical development of a region.

Diamond On The Origin of Capitalism

Going deeper than social relations in production, as in Marx, and also deeper than an inner motivation to steady and industrious labour, as in Weber, is what positions the approach of Jared Diamond far off from established academic approaches. In fact, Marx’ German Ideology contains a passage where Marx explicitly mentions the influence of ‘natural’ factors such as the distribution of water – only to do away with it rather quickly it as his focus is not on nature, but on the social dynamics of working under the division of labor.

The same passage by Marx acts as the starting point of Guns, Germs And Steel. By considering the groundbreaking influence of domesticable plants and animals Diamond is able to make out those regions of the world that were more likely to see an advanced economic development, as well as those who ‘by nature’ had a late start they could never make up for. In fact, Diamond states that a solid food production as the basis for the transition of an egalitarian hunter and gatherer society to a differentiated one based on farming. A more differentiated society with a surplus in food production sees the rise of a dominating class that is ruling over the majority of unarmed commoners, a form of society which Diamond, now in line with orthodox Marxist theory, refers to as a kleptocracy.

What Jared Diamond deserves credit for is to have expanded the classic rivalry between objectivism (structure, economics) and subjectivism (the History of Big Men) for a third, nature-related approach that seeks out the very foundations of how a capitalist structure could develop in the first place.

As Diamonds points out it is a combination of physiology and geography that laid out the underlying foundation of what what many other social theories are not even aware of.

Leave a Reply